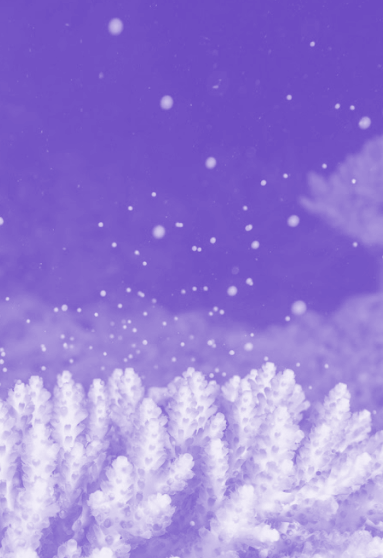

Coral window widened

Australian scientists have, for the first time, bred captive corals months outside of their natural reproductive window.

Australian scientists have, for the first time, bred captive corals months outside of their natural reproductive window.

Researchers from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) have successfully bred a new generation of captive-raised corals in an experimental aquarium outside, months before the annual spawning season on the Great Barrier Reef later this year.

The annual spawning event normally takes place on a handful of nights following the full moon in November or December where corals on the Reef reproduce en-masse in one of the most extraordinary natural phenomena on the planet.

This means that researchers get only one window of opportunity per year to capitalise on the spawning to research issues vital to the future of the Great Barrier Reef.

Having multiple spawning events a year opens opportunities for marine scientists to fast-track knowledge development around coral biology to help protect reefs from the effects of climate change.

Corals are guided by environmental cues such as temperature, day length and moon phase, to release eggs and sperm into the water, to create new coral larvae.

Senior aquarist at AIMS’s National Sea Simulator (SeaSim) in Townsville, Lonidas Koukoumaftsis, says researchers have now replicated the same environmental conditions that prompt spawning on the Reef and applied them to captive corals from six species reared at the facility since 2014.

“These corals have never been exposed to natural environmental cues. They have been raised under artificial conditions all their lives,” he said.

A team of research technicians induced 43 corals from the six species to spawn months before the normal ‘spawning season’, and four hours earlier in a typical spawning evening.

The team’s success continued when the egg and sperm bundles fertilised, larvae settled and grew to become young corals, closing the life cycle in captivity for four of the six coral species.

AIMS ecologist Dr Carly Randall says the ability to control the timing of corals’ reproductive cycle is key to bypassing the bottleneck of seasonal larval supply, with implications for both coral aquaculture and research applications.

“The ability to obtain coral larvae multiple times a year allows scientists to undertake research that is critically needed to determine how best to help reefs recover from disturbances,” she said.

“At-scale reef adaptation and restoration is a race against time.

“The ability to control the timing and frequency of spawning in the lab increases research opportunities to stay ahead of the curve and accelerate the development of feasible options to protect the Great Barrier Reef from some of the effects of climate change.

“If marine science and research can delay coral decline by 20 years, we have created a significant window of opportunity for climate adaptation measures to produce solutions and for global initiatives to curb emissions.”

The National Sea Simulator supports rearing and long-term propagation of different coral species, allowing multi-generational studies, which are becoming critical in understanding how marine organisms can adapt to a changing environment.

Print

Print