Curious minds create changed climate

Researchers have created a climate change microcosm to see how the ecosystem will respond.

Researchers have created a climate change microcosm to see how the ecosystem will respond.

Figuring out how ecosystems will respond to climate change is tricky, so British researchers working in Antarctica have created the warming themselves.

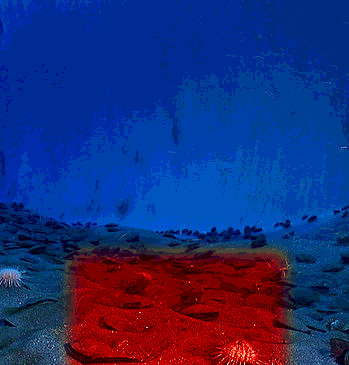

Using heated panels, they warmed an area of seabed to 1 or 2 degrees Celsius above the ambient temperature and measured changes in the ecosystem.

At 1°C warming, a single species of bryozoan took off — ultimately dominating the community within two months and reducing other species' abundance.

At 2°C warmer, the growth rates were more variable among different species. The researchers said they were surprised at the rate of change, considering many temperate climates experience much greater temperature fluctuations.

They say their findings suggest a warming planet could have greater effects on polar marine ecosystems than anticipated, creating winners and losers between species.

“I was quite surprised,” says Gail Ashton of the British Antarctic Survey and Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

“I wasn't expecting a significant observable difference in communities warmed by just 1°C in the Antarctic.

“I have spent most of my career working in temperate climates where communities experience much greater temperature fluctuations and wasn't expecting such a response to just 1°C of change.”

With a 1°C increase in temperature, a single pioneer species of bryozoan (Fenestrulina rugula) went wild, and grew to dominate the community, driving a reduction in overall species diversity and evenness within two months.

Individuals of a marine worm, Romanchella perrieri, also grew to an average size 70 per cent larger than those under ambient conditions, the researchers report.

The responses of organisms to a 2°C rise in temperature were much more variable.

Growth-rate responses to warming differed among species, ages, and seasons. Species generally grew faster with warming through the Antarctic summer. However, different responses among species were observed in March, when both food availability for suspension feeders and ambient temperature declined, the researchers report.

Print

Print