Immutable microbes uncovered

Ocean researchers have discovered a microbe that has not evolved for millions of years.

Ocean researchers have discovered a microbe that has not evolved for millions of years.

Research led by Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences has revealed that a group of microbes, which feed off chemical reactions triggered by radioactivity, have been at an evolutionary standstill for millions of years.

“This discovery shows that we must be careful when making assumptions about the speed of evolution and how we interpret the tree of life,” says Dr Eric Becraft, the lead author on the paper.

“It is possible that some organisms go into an evolutionary full-sprint, while others slow to a crawl, challenging the establishment of reliable molecular timelines.”

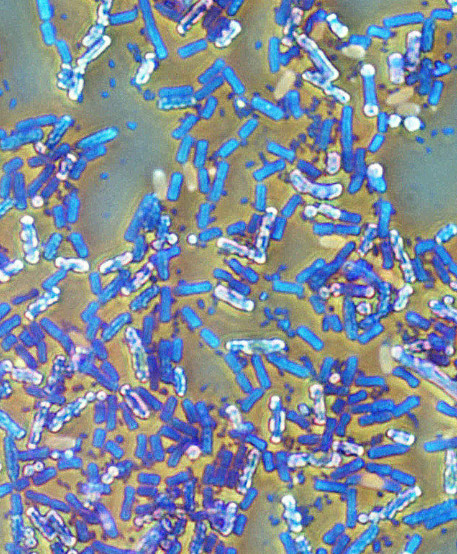

The microbe, Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator, was first discovered in 2008 in a South African gold mine almost two miles beneath the Earth's surface.

The microbes feed off chemical reactions caused by the natural radioactive decay in minerals. They live in water-filled cavities inside rocks, forming a completely independent ecosystem, free from reliance on sunlight or any other organisms.

Researchers then discovered Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator in Siberia and California, as well as in several additional mines in South Africa.

Since each environment was chemically different, the discoveries gave the researchers a unique opportunity to look for differences between the populations over their millions of years of evolution.

The researchers sequenced the genomes of 126 microbes from three continents. Surprisingly, they all turned out to be almost identical.

Scientists found no evidence that the microbes can travel long distances, survive on the surface, or live long in the presence of oxygen. So, once researchers determined that there was no possibility the samples were cross-contaminated during research, plausible explanations dwindled.

“The best explanation we have at the moment is that these microbes did not change much since their physical locations separated during the breakup of supercontinent Pangaea, about 175 million years ago,” said researcher Ramunas Stepanauskas.

“They appear to be living fossils from those days. That sounds quite crazy and goes against the contemporary understanding of microbial evolution.”

Some of the most common bacteria, such as E. coli, can evolve in only a few years in response to environmental changes, such as exposure to antibiotics.

But the researchers hypothesise that the paused evolution they discovered is due to the microbe's powerful protections against mutation, which have essentially locked their genetic code.

The finding could even help improve human genetic therapies.

Microbial enzymes that create copies of DNA molecules, called DNA polymerases, are widely used in biotechnology. Enzymes with high fidelity, or the ability to recreate themselves with little differences between the copy and the original, are especially valuable.

“There's a high demand for DNA polymerases that don't make many mistakes,” Stepanauskas said.

“Such enzymes may be useful for DNA sequencing, diagnostic tests, and gene therapy.”

Beyond potential applications, the results of this study could have far-reaching implications and change the way scientists think about microbial genetics and the pace of their evolution.

“These findings are a powerful reminder that the various microbial branches we observe on the tree of life may differ vastly in the time since their last common ancestor,” Dr Becraft said.

“Understanding this is critical to understanding the history of life on Earth.”

Print

Print