Pollution linked to brain effect

Tiny particles in air pollution have been linked to the development of Alzheimer’s.

Tiny particles in air pollution have been linked to the development of Alzheimer’s.

Magnetite, a tiny particle found in air pollution, can induce signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, new research suggests.

Alzheimer’s disease, a type of dementia, leads to memory loss, cognitive decline, and a marked reduction in quality of life. It impacts millions globally and is a leading cause of death in older people.

A new study has examined the impact of air pollution on brain health in mice, as well as in human neuronal cells in the lab.

“Fewer than 1 per cent of Alzheimer’s cases are inherited, so it is likely that the environment and lifestyle play a key role in the development of the disease,” says Associate Professor Cindy Gunawan from the Australian Institute for Microbiology and Infection (AIMI).

“Previous studies have indicated that people who live in areas with high levels of air pollution are at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

“Magnetite, a magnetic iron oxide compound, has also been found in greater amounts in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

“However, this is the first study to look at whether the presence of magnetite particles in the brain can indeed lead to signs of Alzheimer’s,” she said.

The researchers exposed healthy mice and those genetically predisposed to Alzheimer’s to very fine particles of iron, magnetite, and diesel hydrocarbons over four months. They found that magnetite induced the most consistent Alzheimer’s disease pathologies.

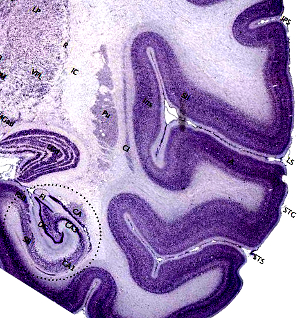

This included the loss of neuronal cells in the hippocampus, an area of the brain crucial for memory, and in the somatosensory cortex, an area that processes sensations from the body. Increased formation of amyloid plaque was seen in mice already predisposed to Alzheimer’s.

The researchers also observed behavioural changes in the mice that were consistent with Alzheimer’s disease including increased stress and anxiety and short-term memory impairment, the latter particularly in the genetically predisposed mice.

“Magnetite is a quite common air pollutant. It comes from high-temperature combustion processes like vehicle exhaust, wood fires and coal-fired power stations as well as from brake pad friction and engine wear,” said Associate Professor Kristine McGrath from the UTS School of Life Sciences.

“When we inhale air pollutant, these particles of magnetite can enter the brain via the lining of the nasal passage, and from the olfactory bulb, a small structure on the bottom of the brain responsible for processing smells, bypassing the blood-brain barrier,” she said.

The researchers found that magnetite induced an immune response in the mice and in the human neuronal cells in the lab.

It triggered inflammation and oxidative stress, which in turn led to cell damage. Inflammation and oxidative stress are significant factors known to contribute to dementia.

“The magnetite-induced neurodegeneration is also independent of the disease state, with signs of Alzheimer’s seen in the brains of healthy mice,” said Dr Charlotte Fleming, a co-first author from the UTS School of Life Sciences.

The results will be of interest to health practitioners and policymakers.

It suggests that people should take steps to reduce their exposure to air pollution as much as possible, and consider methods to improve air quality and reduce the risk of neurodegenerative disease.

The study also has implications for air pollution guidelines.

The experts say magnetite particles should be included in the recommended safety threshold for air quality index, and increased measures to reduce vehicle and coal-fired power station emissions are also needed.

Print

Print