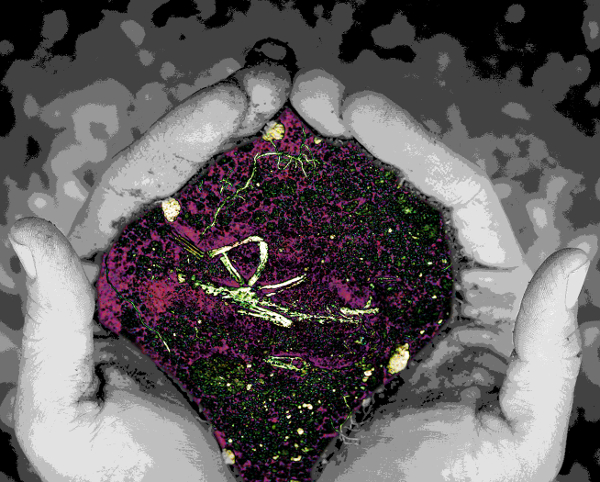

Soil sounds for health check

Beneath the surface, the soil is hosting a silent rave of bubbles and clicks.

Beneath the surface, the soil is hosting a silent rave of bubbles and clicks.

Researchers at Flinders University in Australia are pioneering a new method for measuring soil biodiversity by recording the barely audible sounds of underground ecosystems.

These sounds resemble an “underground rave concert”, according to microbial ecologist Dr Jake Robinson.

The research, led by Dr Robinson and his team at the Frontiers of Restoration Ecology Lab, captures a chaotic mixture of soundscapes produced by small animals in the soil.

Their movement and interactions with their environment generate distinct sounds, providing insights into the health of soil ecosystems.

This field, known as ‘eco-acoustics’, is still in its early stages, but it shows promise as a tool to detect and monitor soil biodiversity.

“Restoring and monitoring soil biodiversity has never been more important,” says Dr Robinson, with 75 per cent of the world’s soils currently classified as degraded.

He adds that almost 60 per cent of Earth’s species live underground, highlighting the importance of understanding these ecosystems.

“All living organisms produce sounds, and our preliminary results suggest different soil organisms make different sound profiles depending on their activity, shape, appendages and size,” he said.

The study involved passive acoustic monitoring in the Mount Bold region of South Australia.

Using below-ground sampling devices and sound attenuation chambers, researchers recorded the sounds produced by various soil invertebrates, such as ants, beetles, and spiders.

The acoustic data was compared across different soil conditions: degraded plots, remnant vegetation, and areas that had been revegetated 15 years ago.

Findings indicated that the acoustic complexity and diversity were higher in revegetated and remnant plots compared to cleared areas.

The richness of the sounds correlated with the abundance and diversity of soil invertebrates.

“It’s clear acoustic complexity and diversity of our samples are associated with soil invertebrate abundance - from earthworms, beetles to ants and spiders - and it seems to be a clear reflection of soil health,” Dr Robinson notes.

The study, which also involved Professor Xin Sun from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supports the notion that eco-acoustic monitoring could become a valuable tool for soil health assessments.

With increasing pressure to restore degraded lands globally, this research provides a new method for evaluating biodiversity in ecosystems undergoing restoration.

Experts say there is a global need for effective soil biodiversity monitoring.

Current approaches, which often involve manual counting or chemical analysis, can be invasive and resource-intensive.

In contrast, acoustic monitoring is non-invasive and could provide real-time data on soil health, making it an attractive option for land managers and conservationists.

As the field of eco-acoustics evolves, the researchers say it is likely to play a crucial role in the future of environmental conservation, providing insights into some of the Earth’s most hidden and critical ecosystems.

The full research paper is accessible here.

Print

Print