Spider silk saves key protein

Swedish scientists say spider silk can stabilise a cancer-suppressing protein.

Swedish scientists say spider silk can stabilise a cancer-suppressing protein.

A protein known as ‘p53’ has been shown to protect cells from cancer, making it an interesting target for cancer treatments.

However, there is a problem - the p53 protein breaks down rapidly in the cell.

But now, researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet have found an unusual way of stabilising the protein and making it more potent.

By adding a spider silk protein to p53, they have found that it is possible to create a protein that is more stable and capable of killing cancer cells.

“The problem is that cells only make small amounts of p53 and then quickly break it down as it is a very large and disordered protein,” says one of the study’s authors, Michael Landreh.

“We’ve been inspired by how nature creates stable proteins and have used spider silk protein to stabilise p53. Spider silk consists of long chains of highly stable proteins, and is one of nature’s strongest polymers.”

The medical experts reached out to other scientists that were already using spider silk in their research, who suggested attaching a small section of a synthetic spider silk protein onto the human p53 protein.

When they then introduced it into cells, they found that the cells started to produce it in large quantities.

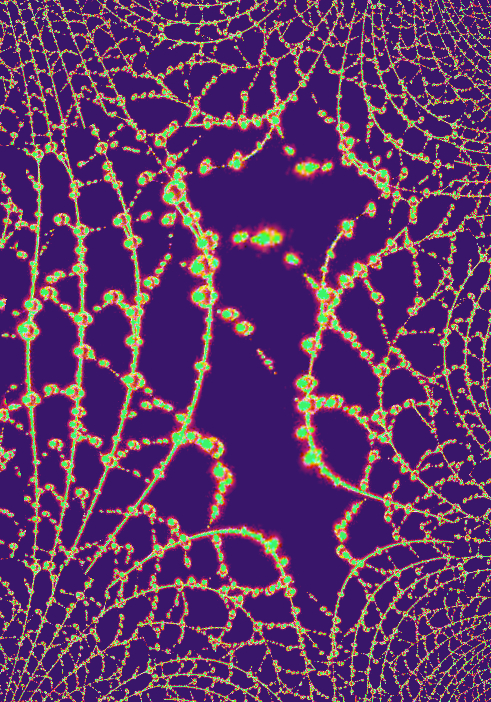

The new protein also proved to be more stable than ordinary p53 and capable of killing cancer cells. Using electron microscopy, computer simulations, and mass spectrometry, they were able to show that the likely reason for this was the way the spider silk part managed to give structure to p53’s disordered sections.

The researchers now plan to study the protein’s structure in detail and how its different parts interact to prevent cancer. They also hope to find out how the cells are affected by the new potent p53 protein and how well they tolerate its spider-silk component.

Professor Sir David Lane. Photo: Ulf Sirborn

Sir David Lane. Photo: Ulf Sirborn

“Creating a more stable variant of p53 in cells is a promising approach to cancer therapy, and now we have a tool for this that’s worth exploring,” says co-author and senior professor Sir David Lane at Karolinska Institutet.

“We eventually hope to develop an mRNA-based cancer vaccine, but before we do so we need to know how the protein is handled in the cells and if large amounts of it can be toxic.”

The full study is accessible here.

Print

Print